The term meningioma is a name for a tumor of the meninges, which are membranes that line the skull and enclose the brain. Meningiomas may arise from any location where meninges exist (eg, nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, middle ear, mediastinum) and are generally thought to be slow-growing and benign. A meningioma can vary in size from a few millimeters to many centimeters in diameter.

Meningiomas account for 15 to 20% of intracranial tumors and 90 percent of meningiomas are intracranial. They commonly occur in the fourth through sixth decades of life. They are more common in females and are rare in children.

Olfactory groove meningiomas grow along the nerves that run between the brain and the nose, the nerves allow you to smell. They can become large without causing significant neurologic deficits or evidence of increased intracranial pressure. Loss of smell can often be the only symptom. Changes in mental status are seldom striking until the tumor has reached a large size. Once the tumor becomes large it impinges on the optic nerves and chiasm resulting in visual loss.

Meningiomas of the sphenoid wing are traditionally divided into three types: lateral (outer), middle, and medial (inner). The outer sphenoid wing meningiomas are usually accompanied by epilepsy, focal weakness, and trouble with language function when present on the left side. The tumors of the medial (inner) sphenoid ridge usually compress the optic nerve and present with early unilateral visual loss. They also may involve the cavernous sinus to cause double vision and numbness of the face.

Causes

As with almost all other types of brain tumors, the cause of meningiomas is not well understood, but possibilities that have been suggested include:

• Radiation, especially in children. There are cases of meningiomas forming under a fracture, area of scarred dura or around a foreign body.

• Patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease tend to develop multiple meningiomas at a young age. In these cases chromosomal aberrations are regularly seen.

• Hormonal factors may play a role in the genesis of meningiomas; both estrogen and progesterone receptors have been found in meningioma preparations.

Symptoms

Symptoms are caused by compression of brain or spinal cord. The tumor has a predilection for certain regions and produces symptoms and signs specific to the tumor’s location. The clinical course of a meningioma characteristically spans a period of years.

Olfactory groove meningiomas often cause a loss of the sense of smell. If they grow large enough, they can also compress the nerves to the eyes, causing visual symptoms as well.

Sphenoid meningiomas (meningiomas growing on the optic nerve behind the eyes) can cause visual problems, including loss of patches within your field of vision, or even blindness. In addition, they can cause loss of sensation in the face, or facial numbness.

The indications for surgical treatment have been the presence of neurological symptoms or certain image findings, which may include

• Changes in mental function

• Headaches

• Disturbances in vision

• Seizure disorders

• Asymptomatic patient with edema in the adjacent brain areas, or

• MRI findings that the meningioma is near the optic nerves.

Rarely does the patient report loss of sense of smell as a symptom, although it is usually documented on examination. However, if olfaction is still present the patient should be warned about the loss of this function, since acute loss may be quite bothersome.

Diagnosis

Standard x-rays are often valuable in detecting meningiomas.

In 50% to 60% of patients, the diagnosis may be suspected from the changes shown on skull radiographs.

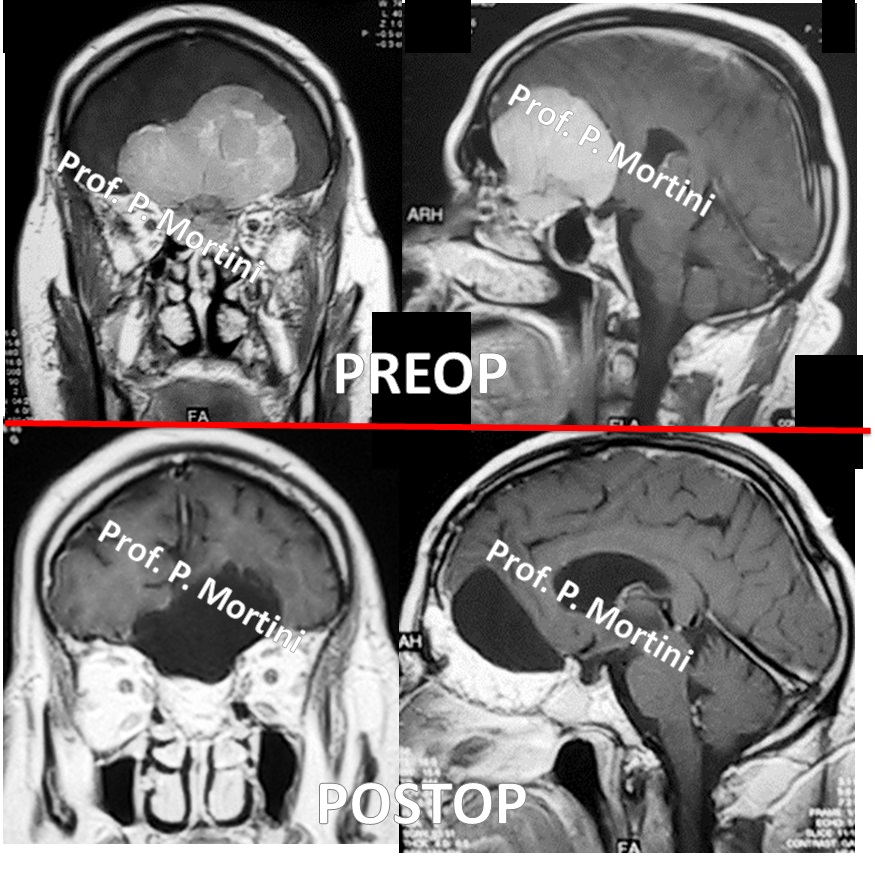

CT is a definitive diagnostic method that shows the tumor as a homogeneously contrast-enhancing mass with well defined borders.

MRI, particularly with contrast, can superbly demonstrate the meningioma and its relationship to neural and vascular structures.

Angiography demonstrates the tumor’s vascularity and its blood supply in preparation for surgery and possible pre-operative embolization. Angiography also can determine the extent of encasement of the internal carotid artery and its branches. On rare occasions, especially with recurrence of an aggressive tumor, internal carotid occlusion is considered prior to surgery. Embolization of external carotid artery branches may occasionally be indicated.

Treatment

The treatment decisions are often difficult. Prior to the development of CT and MRI and microsurgical techniques it was difficult to remove these tumors completely and the risks of surgery were very high. With the development of microsurgical techniques, some of these tumors now can be extensively removed. It remains to be established in the long term which patients benefit more from this extensive surgery with the increased risk of morbidity, from a partial removal of tumor followed by radiation therapy, or from radiation therapy alone.

Treatment options include observation, surgery and radiation.

• Observation: Small tumors in older patients that do not cause symptoms can be followed with yearly MRI scans. Since these tumors are benign and slow growing they may not cause any problems during the life span of some patients.

• Surgery: In younger patients, in critical locations, and when these tumors cause symptoms (including seizures), surgical removal is the best treatment option. While every effort is aimed at total removal, certain tumors present a formidable technical challenge because they adhere to vital neural and vascular structures at the base of the brain. Sphenoid tumors, for example, can sometimes involve the blood sources of the brain (e.g. cavernous sinus, or carotid arteries), making them difficult or impossible to completely remove. They also can grow to a large size before being diagnosed due to changes in the sense of smell and mental status changes being difficult to catch.

• Radiation: For tumors in regions that are difficult to access or in patients who are at considerable risk for surgery, radiation therapy is an option. Radiation is best given as stereotactic radiosurgery. For benign meningiomas, radiation is thought to be helpful in palliating inoperable tumors, residual nonresectable tumors, and recurrent nonresectable tumors. In some cases, radiation therapy may not be recommended as a primary treatment and would be used only to treat recurrence following radical subtotal removal.

Prognosis

Meningiomas are known to recur. Many factors relate to recurrence, the most important of which is the extent of the original removal. Complete resection including removal of the dural margin is associated with a low rate of recurrence. Naturally, more aggressive and metastatic meningiomas are associated with an increased rate of recurrence based on the biology of their cellular components.

English

English Italiano

Italiano